The Mello-Moods

By Marv Goldberg

Based on interviews with James Bethea,

Bobby Baylor and Monte Owens.

© 2001, 2009 by Marv Goldberg

Years before there was Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, there was another "kid group." But what a difference! Whereas, by their very name, the Teenagers were directed at the ever-increasing "teenagers with money to spend" market, the Mello-Moods were singing adult songs aimed at an adult market. However, just like with the Castelles, we've tended to lower the age of the lead singer until he fit into our concept of the "Frankie Lymon" mold.

There must have been youthful singers, even groups, before the Mello-Moods, but they never attained any popularity in the "Race" music, or early R&B field. Among vocal groups, mature men, such as the Mills Brothers and Ink Spots (in their 20s and approaching dotage), dominated the scene until the somewhat younger Ravens and Orioles emerged in the late forties. But even these groups, who were defining the R&B sound, were mature-sounding in comparison to the relatively child-like quality of the Mello-Moods. Says James Bethea: "We were the youngest professional group out there."

The start of the group that was to become the Mello-Moods goes back to 1949 or 1950. There were benches in the newly-built Harlem River Houses (a housing project on West 151st Street and 7th Avenue), and on these, four young kids started singing: Raymond "Buddy" Wooten (first tenor and lead; no one ever called him Ray), Bobby Williams (second tenor, second lead, and piano), Alvin "Bobby" Baylor (second tenor and baritone), and Monteith "Monte" Owens (tenor, baritone, and guitar). They all attended Resurrection Grammar School, also on West 151st Street, mostly as eighth graders. (They liked to sing on benches, there were others, down by the Harlem River, on which they also practiced.)

One day, as they were practicing on a bench, James Bethea, another resident of the Harlem River Houses (but who was attending Stitt Junior High), overheard them, walked over, and started chiming in on the bass parts. "The next thing I knew, I was singing with them," says James.

Who could have served as an inspiration to young teenagers in 1950? Not too surprisingly it was Sonny Til and the Orioles. The newly formed Mello-Moods would harmonize on "It's Too Soon To Know," "A Kiss And A Rose," and even "Donkey Serenade." One song that the Orioles did at shows (which they never got around to recording) was an up-tempo version of Frank Loesser's "Where Are You (Now That I Need You)." The guys liked that one, and for about a year practiced the song up-tempo, using more of a unison arrangement than harmony.

Not only did they practice on those benches, but also in Macombs Dam Park, behind Yankee Stadium, right next door in the Bronx. Then there were the apartments of Bobby Williams and James Bethea, since both had pianos. Their big numbers were "Where Are You" and "Bewildered" (which Monte would lead).

James' sister and her friend met a couple of guys from another group: Jimmy Keyes and Demetrious Clare. They came to James' apartment, listened, and liked the sound they heard. One piece of advice they gave Buddy was to slow down "Where Are You." Keyes and Clare ended up as coaches to the fledgling group.

About a year after they formed, a friend heard that record store owner Bobby Robinson was starting a record company. They went to meet him and he ended up coming to one of their rehearsals. The astute Robinson, with a sharp eye for talent, obviously recognized the potential of recording a young group. He introduced them to former tap dancer Joel Turnero, who became their manager (by this time, Jimmy Keyes was busy forming the Chords).

About a year after they formed, a friend heard that record store owner Bobby Robinson was starting a record company. They went to meet him and he ended up coming to one of their rehearsals. The astute Robinson, with a sharp eye for talent, obviously recognized the potential of recording a young group. He introduced them to former tap dancer Joel Turnero, who became their manager (by this time, Jimmy Keyes was busy forming the Chords).

Up till now, the group had existed with no name. Since Bobby Robinson's new label was to be called Robin Records, he first called the untitled group "The Robins," but that didn't last too long. He later changed it to "The Mello-Moods."

Around November 1951, the Mello-Moods recorded their first two tunes: "Where Are You" and "How Could You" (written by Joel Turnero). On the recordings, they were accompanied by the Schubert Swanston Trio. Eddie "Schubert" or "Schubie" Swanston (piano, celesta, and Hammond organ), Jimmy Buchanan (tenor sax) and Maurice "Chink" Hines (drums). Chink Hines, a future manager of the Solitaires, is the father of singer-dancer-actor Gregory Hines. The session took place in a real studio (although James doesn't remember where), not in the back of Robinson's store.

Around November 1951, the Mello-Moods recorded their first two tunes: "Where Are You" and "How Could You" (written by Joel Turnero). On the recordings, they were accompanied by the Schubert Swanston Trio. Eddie "Schubert" or "Schubie" Swanston (piano, celesta, and Hammond organ), Jimmy Buchanan (tenor sax) and Maurice "Chink" Hines (drums). Chink Hines, a future manager of the Solitaires, is the father of singer-dancer-actor Gregory Hines. The session took place in a real studio (although James doesn't remember where), not in the back of Robinson's store.

At the time "Where Are You" was recorded, both Buddy and James had recently turned 16, Bobby Baylor and Monte Owens were about 15, and Bobby Williams brought up the rear at around 12. Like George Grant of the Castelles, Buddy had a voice that sounded young; in fact, both were 16 at their first sessions.

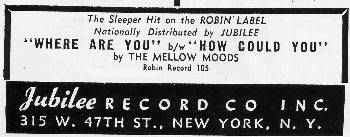

The tunes were released in December as Robin 105. Robin Records were distributed by Jubilee, and ads for "Where Are You" appear along with ads for the Orioles' "Baby Please Don't Go" and Buddy Lucas' "Diane." Note that Robinson issued his first three records using a numbering scheme which assigned only odd numbers to his records: 101, 103, and 105. When the owners of the other Robin Records, in Tennessee, stopped him from using the name, he simply changed it to Red Robin. At that time, Robin 101, 103 and 105 were reissued as Red Robins. (Since a 78 rpm copy of Red Robin 105 has recently surfaced, it's reasonable to assume that number 103 will also turn up someday.) Then he switched to a more conventional system, issuing numbers 102 and 104 on Red Robin. Thus, the second Mello-Moods release would have a lower number than the first.

The tunes were released in December as Robin 105. Robin Records were distributed by Jubilee, and ads for "Where Are You" appear along with ads for the Orioles' "Baby Please Don't Go" and Buddy Lucas' "Diane." Note that Robinson issued his first three records using a numbering scheme which assigned only odd numbers to his records: 101, 103, and 105. When the owners of the other Robin Records, in Tennessee, stopped him from using the name, he simply changed it to Red Robin. At that time, Robin 101, 103 and 105 were reissued as Red Robins. (Since a 78 rpm copy of Red Robin 105 has recently surfaced, it's reasonable to assume that number 103 will also turn up someday.) Then he switched to a more conventional system, issuing numbers 102 and 104 on Red Robin. Thus, the second Mello-Moods release would have a lower number than the first.

"Where Are You" received a good review the week of December 29, 1951. Other songs reviewed that week were: the Ravens' "Wagon Wheels," Chris Powell's "October Twilight," Little Richard's "Every Hour," and the Majors' "Laughing On The Outside, Crying On The Inside." By the time it left the R&B charts, "Where Are You" had made it to #7.

Soon after the release of the record, Bobby Baylor, who'd been missing rehearsals, was asked by Turnero to leave the group. When I spoke to Bobby, he admitted that he wasn't taking his responsibilities as seriously as he should have, but it was one of the saddest days in his life. He immediately formed a group of his own, the Hi-Lites, on 142 Street and Edgecombe Avenue.

The Mello-Moods were now a quartet, although their second record for Robinson still identified them as "vocal quintet"; there were no further personnel changes.

With a hit record to their credit, you'd think that the Mello-Moods would have been swamped with personal appearances. However, remember that they were young and their parents watched them like hawks. School was the most important thing, and anything that stood in its way was to be squashed. Also, they couldn't appear at any place that sold alcohol. As James says, "Our parents wouldn't let us out of their sight. They fought tooth and nail with Joel Turnero and Bobby Robinson."

With a hit record to their credit, you'd think that the Mello-Moods would have been swamped with personal appearances. However, remember that they were young and their parents watched them like hawks. School was the most important thing, and anything that stood in its way was to be squashed. Also, they couldn't appear at any place that sold alcohol. As James says, "Our parents wouldn't let us out of their sight. They fought tooth and nail with Joel Turnero and Bobby Robinson."

They entered the Apollo amateur show. They were in the basement practicing, and a little guy came over to listen to them. After hearing them, he said that they were so good he wouldn't even bother to appear on the same show with them. However, he somehow got over his nervousness and went on to "tear the stage up" and win first prize that night. His name? Otis Blackwell. The Mello-Moods had to settle for second place.

They also had auditions for Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts, but were never called to appear. Monte Owens remembered that the Mello-Moods appeared on an early TV show called "Spotlight On Harlem," which was M.C.'d by DJ Ralph Cooper (WOV). They also appeared with Earl Bostic on a radio show broadcast from the Hotel Teresa and with Nipsey Russell, in a show in downtown New York. Their biggest appearance was at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, along with Ruth Brown and Willis "Gator Tail" Jackson. More typical of their performances was the YMCA on 135th Street.

One day they did a show early in the morning and then ended up late for school. Buddy used the appearance as an excuse, and, along with James, was sentenced to the glee club. But neither one took it seriously (it wasn't, after all, their kind of music), and they showed up as little as possible.

And then, a bit of disenchantment started to creep in, even at this early date. They had signed three-year contracts with Turnero and Robinson, and now "Joel tried to change our style of singing. He began to have us sing his songs."

Probably in March 1952, the Mello-Moods had their second session. The two songs recorded this time were: "I Couldn't Sleep A Wink Last Night" and "And You Just Can't Go Through Life Alone." The former song, by Harold Adamson and Jimmy McHugh, had been sung by Frank Sinatra in his first film, "Higher And Higher" (1943). The flip was written by Joel Turnero and "Schubert" Swanston.

The record was released in April and doesn't seem to have been reviewed. Its competition at the time was the Royals' "Every Beat Of My Heart," the 5 Keys' "Red Sails In The Sunset," the Dominoes' "Have Mercy Baby," the Swallows' "Beside You," Billy Bunn & the Buddies' "Until The Real Thing Comes Along," Lloyd Price's "Lawdy Miss Clawdy," and Fats Domino's "Goin' Home."

The record was released in April and doesn't seem to have been reviewed. Its competition at the time was the Royals' "Every Beat Of My Heart," the 5 Keys' "Red Sails In The Sunset," the Dominoes' "Have Mercy Baby," the Swallows' "Beside You," Billy Bunn & the Buddies' "Until The Real Thing Comes Along," Lloyd Price's "Lawdy Miss Clawdy," and Fats Domino's "Goin' Home."

In the fall of 1952, Turnero persuaded them to leave Robinson. There was an announcement in the trades that the Mellow-Moods [sic] had been signed by Par Records. This was an affiliate of Prestige Records, for whom they actually ended up recording.

There was a studio on 47th Street, between Third and Lexington Avenues at which Turnero had them rehearse, using "Schubert" Swanston as their trainer. Swanston taught them stage presence (although they had little enough opportunity to put it into practice).

On November 6, 1952, the Mello-Moods, backed by the Teacho Wiltshire Band, recorded four tunes: "Call On Me," "I Tried, Tried, And Tried," "I'm Lost," and "When I Woke Up This Morning." All were led by Buddy Wooten, except for "I Tried, Tried, And Tried," their only up-tempo recording, which was fronted by Bobby Williams. "I'm Lost," by Otis René, had been a 1944 hit for the King Cole Trio; all the other songs were written by Turnero and Swanston.

They were called back to the studio on December 12, where they recorded Mel Tormé's "The Christmas Song" in a modern harmony arrangement behind the Charlie Ferguson Orchestra. Actually, saxophonist Ferguson himself is blowing lead, with the Mello-Moods doing backup vocalizing and whispering some of the lines . The other musicians were Eddie "Schubert" Swanston on piano, Ed "Tiger" Lewis (trumpet), Peck Morrison on bass, and Herb Lovelle on drums. This tune remained in the can until 1996.

While they were there, they did two recordings behind King Pleasure. They backed him on "Jumpin With Symphony Sid" and "Red

Top." However, there were other, non-group versions of those tunes done that day, and those were the ones that were eventually released.

In January 1953, Prestige released "Call On Me" and "I Tried, Tried, And Tried." The record was reviewed the week of January 24, along with Fats Domino's "Nobody Loves Me," Fat Man Matthews & the 4 Kittens' "When Boy Meets Girl," and the Red Caps' "Do I, Do I, I Do." However, it failed to chart.

In June 1953, after James Bethea graduated from Haaren High School, the Bethea family moved from upper Manhattan to Queens. This made rehearsing with the group difficult, and he started to lose contact with them.

The group finally became disenchanted. Says James, "We were in a beautiful neighborhood, but our parents didn't allow us to go out of their sight. Everything was 'going to school.' We had the feeling that Joel was trying to hold us back, but it could have been our parents. We tried to break our contracts with Joel. None of us were happy with the music we were singing; we wanted real R&B. We enjoyed our singing, but there was a personality conflict. We were doing his tunes and we wanted to do other stuff. He was trying to make a Mills Brothers act out of us. Joel wouldn't release us. We realized that the group was going to break up; we had to stop singing in order to break the contract with Joel." In addition, they hadn't received the proper promotion and (surprise, surprise) they never received the royalties they felt they were entitled to.

When it was all over, Bobby Williams and Monte Owens joined former Mello-Mood Bobby Baylor, along with Winston "Buzzy" Willis and Pat Gaston in the Solitaires. Baylor had been part of the Solitaires almost from the beginning (having replaced Eddie "California" Jones), and brought in Williams and Owens to replace two other original members, Rudy Morgan and Nick Anderson. (Lead singer Herman Curtis was the last addition to the group; he'd been with the Vocaleers as "Herman Dunham.") Bobby Williams left the Solitaires in mid-1956 to join Charlie Mingus. Monte Owens would later appear with Jimmy Castor. Buddy, after all the rehearsing and no money, got totally disgusted and lost faith in management. He got [happily] married and gave up singing.

James Bethea tried to continue with singing too. Arthur Murray had vocal studios (apart from their dance studios), and James took some lessons with them (as he'd done prior to joining the Mello-Moods). He also sang at the Boulevard club, but then he too got married and "I sort of gave up on the singing." He did, however, attend Queens College for a year to study how to read and write music.

Around October, probably after the Mello-Moods had ceased to exist, Prestige issued "I'm Lost" and "When I Woke Up This Morning." The record was never reviewed, but it faced competition from the Orioles' "In The Mission Of St. Augustine," the Crickets' "I'm Not The One You Love," the 4 Tunes' "Marie," the Hunters' "Down At Hayden's," the Love Notes' "Surrender Your Heart," the Ravens' "Without A Song," Otis Blackwell's "Daddy Rollin' Stone," the Royals' "I Feel That-A-Way," the Wanderers' "Hey, Mae Ethel," the Blue Jays' "White Cliffs Of Dover," the Robins' "Ten Days In Jail," and the Flamingos' "Golden Teardrops" (which received a lower rating than its flip, "Carried Away").

Monte Owens identified two essential differences between the Mello-Moods and their successors. First, the Mello-Moods were singing for adults rather than for teenagers and sub-teens. The affluent teenager market was half a decade away when the Mello-Moods were beginning. Secondly, the subject matter of the Mello-Moods' songs was of a serious, more mature nature. "Where Are You" was an old Pop standard; "I Couldn't Sleep A Wink Last Night" was not exactly a sentiment expressed by a 13-year-old. The Teenagers' "I'm Not A Juvenile Delinquent" could more easily become the teenage national anthem than a song of unrequited love, such as "How Could You."

Bobby Williams passed away in 1961, the victim of a blood disease. Bobby Baylor is also gone. The wonderful voice of Ray Wooten was stilled in April, 2006. Monte Owens passed away in March 2011. That leaves Jimmy Bethea as the only survivor.

The Mello-Moods were the first successful young teenage group and therefore occupy a unique position in the history of R&B. Says James, "The group was a lot of fun; we loved singing." [Photo courtesy of Jerry Skokandish.]

The Mello-Moods were the first successful young teenage group and therefore occupy a unique position in the history of R&B. Says James, "The group was a lot of fun; we loved singing." [Photo courtesy of Jerry Skokandish.]

Special thanks to Ronnie Italiano, Billy Vera, and Victor Pearlin.

ROBIN

105 How Could You (RW/BW)/Where Are You (RW/BW) - 12/51

RED ROBIN

104 I Couldn't Sleep A Wink Last Night (RW/BW)/And You Just Can't Go Through Life Alone (RW/BW) - 4/52

PRESTIGE

799 Call On Me (RW/BW)/I Tried, Tried And Tried (BW/RW) - 1/53

856 I'm Lost (RW/BW)/When I Woke Up This Morning (RW) - ca. 10/53

UNRELEASED PRESTIGE

The Christmas Song

LEADS: RW = Ray "Buddy" Wooten; BW = Bobby Williams